In January this year, as part of our annual predictions for the year ahead, we identified the rise of AI as something that was set to impact TV production in 2023. As we enter the final quarter of 2023, it’s interesting to see how close to reality that prediction has come.

We titled that prediction ‘The AI Revolution will be Televised’ and in a follow-up blog post, we explored the idea of a future where AI would transform how content is created, delivered, and experienced. While the more ambitious promises made by enthusiasts of the technology have yet to materialise – nobody is generating scripts or broadcast footage without human input just yet – there’s no doubt that AI has embedded itself more successfully in the industry than other recent tech fads such as blockchain and the so-called “metaverse”.

How this will manifest in terms of mainstream TV production remains to be seen, but major companies are investing in the space, if somewhat cautiously. In August, Banijay announced its AI Creative Fund, offering additional funding to creators across its 21 territories “to create formats which push the boundaries of creativity using Artificial Intelligence and technology”. Notably, the announcement doesn’t specify how AI specifically might be used or put a figure to the investment.

In Korea, as detailed in our recent KOCCA report, the Storypia platform developed by Metauniverse can ingest a script and predict its likely popularity with audiences by analysing scenes, character, timing and more. A future iteration of the software will apparently be able to automatically suggest and generate basic storyboards based on the scene descriptions. UK production company Particle 6 already uses ChatGPT to suggest episode topics, synopses and structures for its Sky Kids pre-school show Look See Wow!.

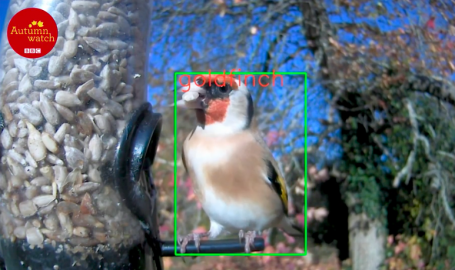

While most of the attention has inevitably been lavished on AI’s ability to ideate and generate content, it’s arguably the least developed aspect of the technology. The BBC has been using AI on its Springwatch and Winterwatch nature programming for several years (pictured), developing bespoke software that can monitor live video feeds, learn how to recognise different animals and birds, and begin filming when the required wildlife is in frame. It can also log and analyse the frequency of particular creatures, saving the production team hours of manual research.

Of course, all of this progress hasn’t come without some degree of pushback. The use of AI, both in generating scripts and reproducing faces and likenesses, has been a hot topic in the WGA and SAG-AFTRA strikes. Louis Theroux’s thought-provoking MacTaggart Lecture at this year’s Edinburgh Festival highlighted the same risks of an over-reliance on AI within the television industry, eliminating the human element and regurgitating digitally remixed variations on existing ideas.

Perhaps more concerning for production companies is the result of a lawsuit in August, after the US Copyright Office repeatedly refused a copyright to computer scientist Stephen Thaler for imagery generated by his Creativity Machine AI program. Thaler sued, but the Copyright Office’s original ruling was upheld by a federal judge, setting a precedent that will need to be overcome if generative AI content is to have any commercial value. After all, no studio wants to find that they do not technically own their latest show format because it was originally generated by a machine rather than pitched by a human being.

For the sake of perspective, it’s also worth remembering that while “AI” is the name that has caught the popular imagination, there’s no real intelligence behind the tools currently available. ChatGPT, Midjourney and others are technically examples of Machine Learning, a sophisticated evolution of predictive text. They ingest enormous quantities of data, analyse their properties and then serve up combinations of the most relevant results based on the user’s prompt. The conversational interface and slick visual results are impressive, and even useful, but it’s risky to assign intent and thought to them.

It remains to be seen how the public will respond to the role of AI in media as it develops. In a June 2023 survey carried out jointly by the Alan Turing Institute and Ada Lovelace Institute to gauge public perception of AI use, media use didn’t even register either negatively or positively, with benefits seen as being mostly in the field of medical diagnosis, particularly cancer, and the threats coming from autonomous vehicles, unmanned military technology and “DeepFake” impacts on politics.

In a fascinating LinkedIn stream at the end of September, The Connected Set’s Jason Mitchell, along with his colleagues Holly Rowlands and Tom Payne, spoke more about how AI tools are already in use by TV producers and freelancers, not as a shortcut to content creation, but as a support system for human creators. “We see AI as a tool for productivity, as a tool to stimulate creativity and it’s a really interesting subject for content,” said Mitchell. “My view is these are not going to replace our jobs, but like any other productivity tool, they will become part of our jobs so understanding [AI tools] will really give you a competitive edge.”

So for now, it seems television has the space and drive to keep investigating ethical ways to incorporate this new field. While some on the fringe fantasise about a future in which consumers can simply ask for exactly what they want to watch and have it generated on demand – “Love Island with Marvel superheroes” coming right up – the more mundane reality is that it’s likely to become just another tool, albeit a powerful one, in the tech stack of any media company. A revolution, certainly, but almost certainly a quiet one.

Dan Whitehead

Dan Whitehead