What makes a successful Factual Format, and how can companies sell the international rights to adapt a show which – on the surface – looks like a straightforward fly-on-the-wall access series? In our Tracking the Giants 2022 list of non-scripted formats that have travelled, Factual Formats make up the smallest segment: just 2% compared to 47% Entertainment, 28% Factual Entertainment and 23% Reality.

But get it right and the rewards are there. Belgian company De chinezen have managed it with Emergency Call, a series set in emergency call handling units across the country that never leaves its claustrophobic setting, focuses almost entirely on the faces of the call-takers, and yet somehow manages to be a totally gripping piece of television. It has now been adapted in 12 territories including the US, France, Sweden, Germany and – most recently and remarkably – Japan, where a series is in production for NHK.

K7’s Clare Thompson spoke to Mikhael Cops at De chinezen and Julian Curtis at distributor Lineup Industries to find out how they managed it.

De chinezen was founded in 2011 by Mikhael Cops, Harald Hauben, Elke Neuville and Arnout Hauben, all current affairs producers who’d worked together on a daily magazine show, with human interest stories. Their ambition for the company was to do short and long-form current affairs, history and human interest in a more formatted way, with early efforts including a series of frontline war walks, with little format devices bringing the history and characters to life.

“We often start from ‘how can we replace the voiceover?’”, says Cops. “Answering that question often leads to interesting format devices based on character.”

There was no real focus on international at that stage, but with a commissioner at VRT who was prepared to consider more creative, original shows, the team were encouraged to experiment.

At the time (2016), there were no ‘blue light’ shows on VRT, so De chinezen began working on an idea called 9-5, following people who worked from 9 at night to 5 in the morning, including doctors and ambulance workers. They had already built some trust through their Radio Gaga series that they were a company who cared about communities and dealt with human stories sensitively.

Having secured access to a 101 (999) emergency call centre and shot a short 15 minute segment of calls, they quickly realised how gripping it was, and went back to get enough for 35 minutes – with everyone who watched still glued until the end. Eventually VRT said they could drop the other elements and Emergency Call went out as just that – becoming an instant hit.

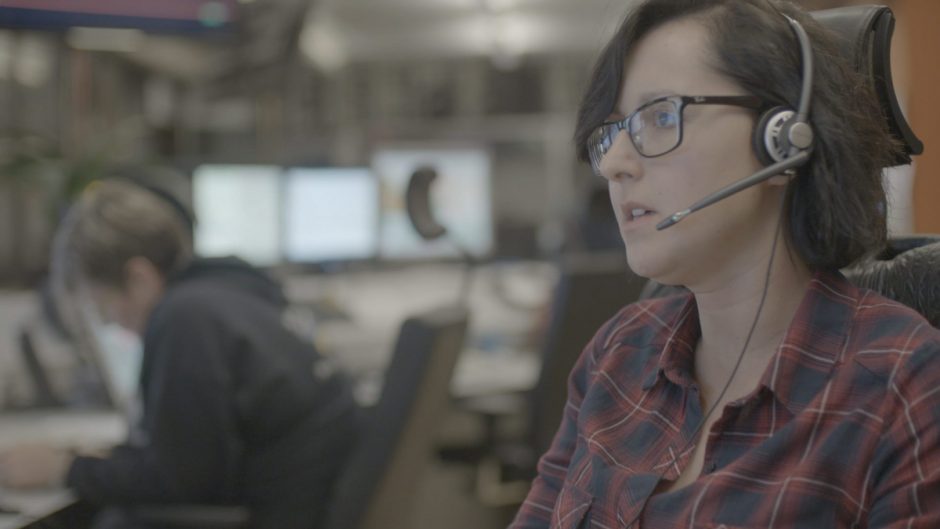

Emergency Call, VRT

Police and ambulance privacy issues were overcome with some dubbing and actors recreating ambulance calls, but the strong relationships built with the emergency services allowed them to be choosy about who they selected to film. And that aspect of the access and casting is key to what they are selling as part of the format’s bible. “It’s a study of the human face. A show where an eye-roll can make a whole story, so casting is key. We’ve found call centres where ten people want to participate but we ditched the whole centre because none were right. They need to be very charismatic, with very expressive faces”, says Cops.

Ed Louwerse at Lineup Industries watched the show go out on VRT and immediately thought it could be sold as a format. Says Lineup’s Julian Curtis,“It’s about drilling down into how to make it – and therefore saving others the time, effort and money. We realised there was a lot of detail in how it’s done – and the value is in how not to make mistakes or make it boring. Think about what you wish you’d known then and know now – the value of that is what a format like this is worth.”

What makes the show is the distinctive look, the sound design, the claustrophobic atmosphere and the tone. “The value is in the details. It never leaves its environment – the only break of setting is when they go on fag break. In that respect it’s very different to other frenetic blue light shows”, explains Cops.

With these kinds of factual formats it’s that execution that is being sold, not necessarily the idea. On paper, it would be nothing. As Cops remarks, “I like ideas that on paper don’t seem like they would work! Because if it works on paper that’s probably because it’s already on. I like it when you have to make a tape to prove it will. It should NOT make sense at first!”

And it’s also about making that tricky relationship-building and winning of trust really work for you, as the producers found when they got a letter from the Belgian Ministry of the Interior, saying how the show had helped the emergency services discourage the ‘pollution’ of time-waster calls. While ridiculous, drunk, nonsense calls had provided some of the light relief in the show, seeing the call-takers having to deal with them dramatically reduced their incidence. That was a stamp of approval from ‘authority’ and was a huge benefit in selling the format, leading directly to the sale of the format to TRT in Turkey, as their version was partly financed by their Interior Ministry to launch a new emergency number.

But one final word of advice from Cops on developing the next world-beating factual format: “It’s not always beneficial to think ‘internationally’. That kind of thinking doesn’t usually work! We can’t walk past our first client, who is our home buyer. Instead we have to think about that buyer and our domestic audience, and then leave it to the distributor to look at it and think about the international.”

Get that right with something original, locally successful AND tricky to execute, and hopefully the format sales will follow.

Clare Thompson

Clare Thompson